Resources

Filters

Clear

Refinements

Studies:

- All studies

- Invasive Disease Surveillance (IBD)

- Inpatient Carriage (INCA)

- Community Carriage (COCA)

- Evaluation of Accelerated Schedule (PIMMS)

- Hospitalization Administrative Data (IPAD)

- Assessment of Economic Impact (PIES)

Types of content:

- All types

- Communications Resource

- News

- Poster

- Publication

- Video

By type of content:

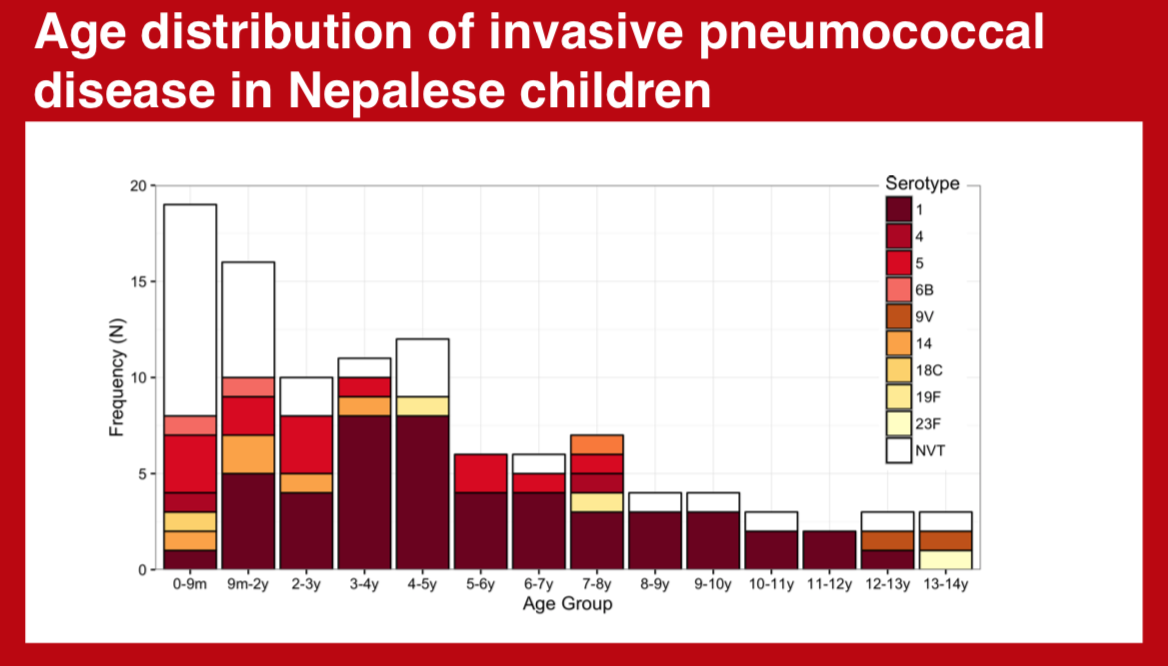

We assessed the distribution of pneumococcal serotypes in children with microbiologicallyconfirmed invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) before (2014-2015) and after(2016-2019) PCV10 introduction in Nepal in 2015.

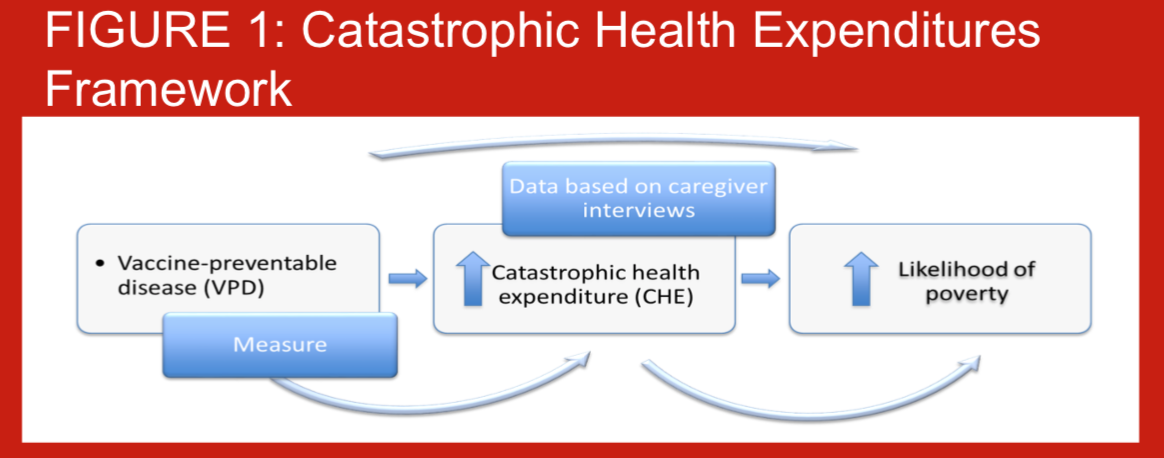

Pneumococcal disease has substantial economic impact on families. Vaccination can prevent disease and provide financial risk protection (FRP). We performed an extended cost-effectiveness analysis of PCV on reducing hospitalizations and catastrophic health expenditures (CHE) in Nepali children.

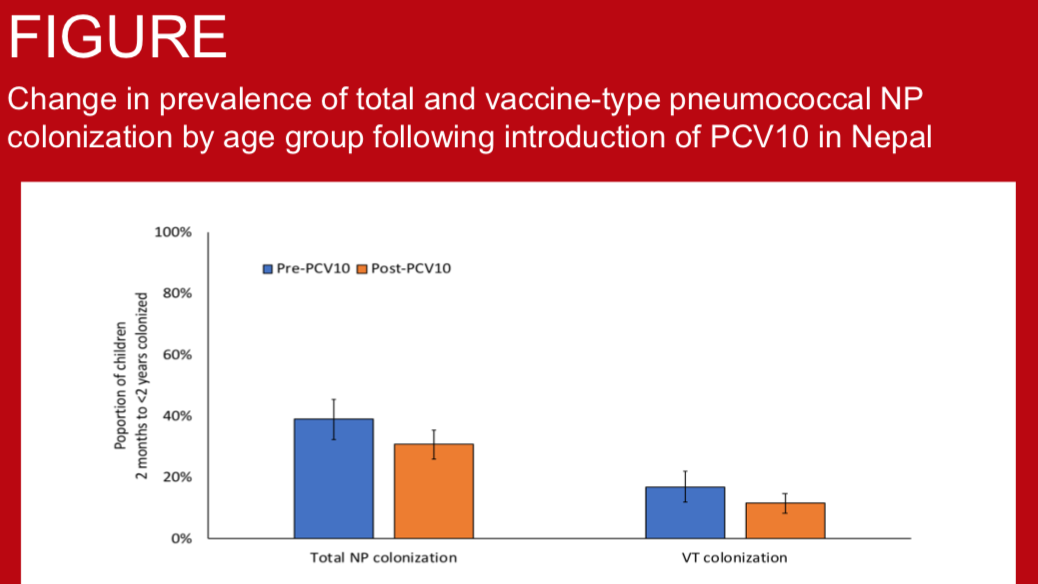

S. pneumoniae is a major cause of bacterial pneumonia and an important cause of invasive bacterial disease (IBD) in children under-five years of age in Nepal. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, PCV10, was introduced in 2015 with a 2+1 schedule. We assessed the programmatic impact of PCV10 introduction using surveillance for nasopharyngeal (NP) colonisation, pneumonia and IBD.

PCV10 was introduced into the infant immunization programme in Nepal in 2015. We assessed the impact of PCV10 on pneumococcal nasopharyngeal carriage in children with pneumonia.

Pneumococcus is one of the most common causes of invasive bacterial disease (IBD), including meningitis, in children. We assessed the impact of PCV10, introduced in Kathmandu October, 2015, on bacterial meningitis in Nepalese children.

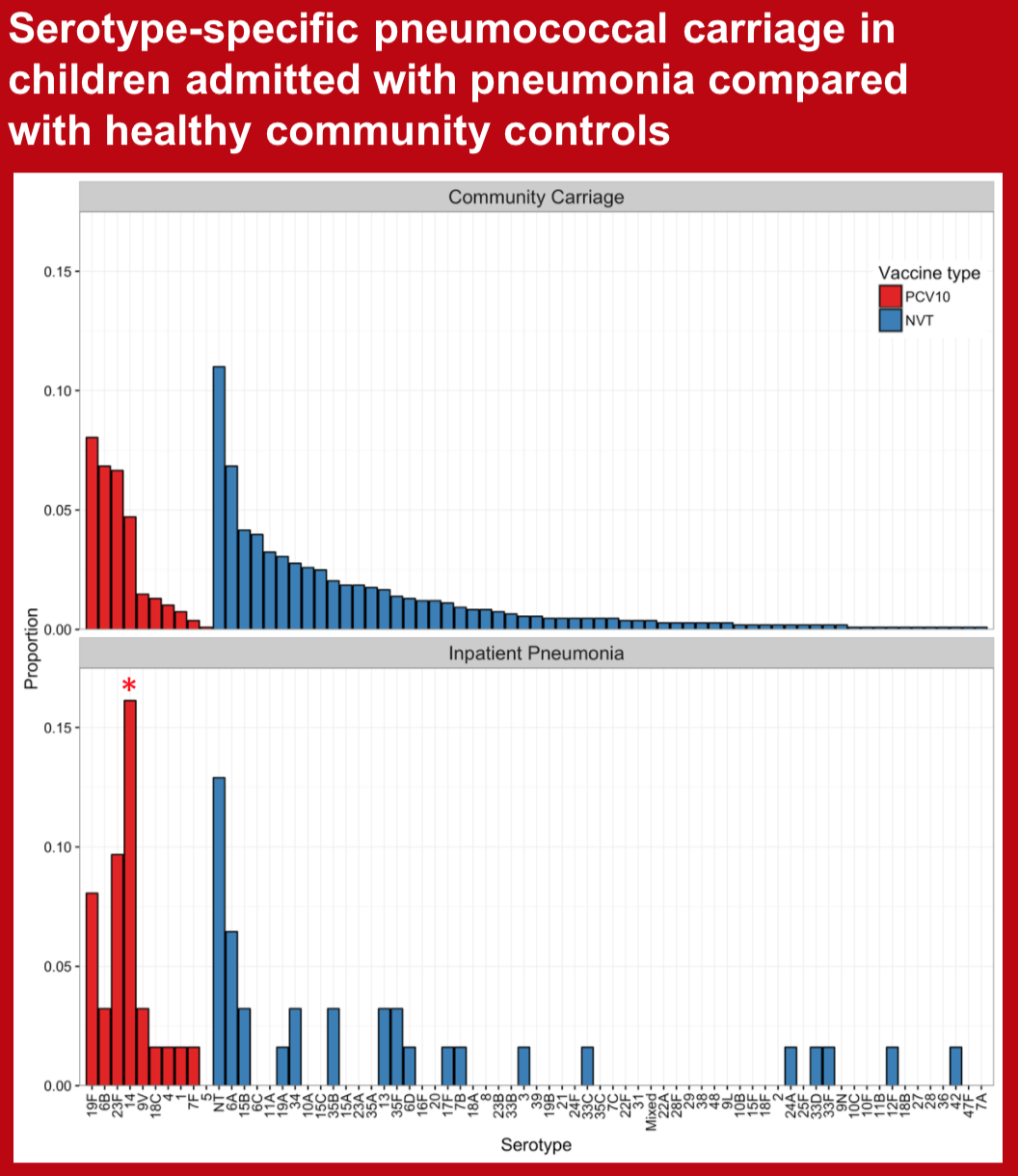

The ten-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine was introduced in Nepal in 2015. We assessed pneumococcal nasopharyngeal carriage and serotype distribution, and the impact of vaccine on them among children with severe and non-severe pneumonia admitted to Patan Hospital, Nepal.

In October 2018, eleven year old Niruta Bishwokarma was hospitalized with severe pneumonia. Nearly two years later, her family still struggles with the emotional and financial consequences of her illness.

Evidence from vaccine research is particularly useful to decision makers, yet many researchers do not prioritize broad dissemination beyond peer-reviewed publication, which limits the audience for results to technical audiences such as those in academia. This toolkit includes resources for stakeholder engagement and storytelling to make data matter, highlighting the PneumoNepal PCV Impact Economic Data Study (PIES) approach as an example. Our resources follow a five-step process that uses stakeholder mapping and audience-specific messaging techniques.

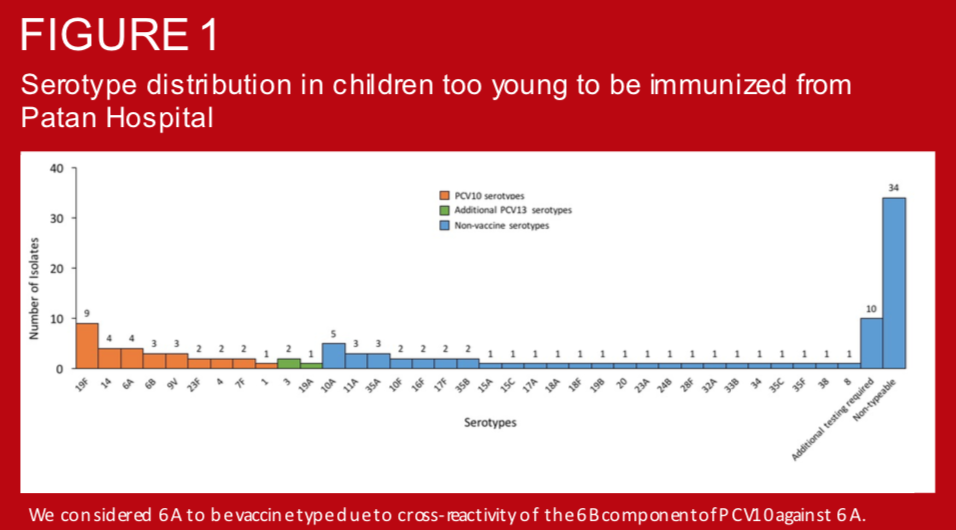

In August 2015, Nepal introduced 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV10) using a 2+1 schedule as follows: 6 weeks, 10 weeks, and 9 months. Children less than 1 year were eligible for catch-up immunization at the time of introduction. Several studies have demonstrated the impact of PCV on vaccine-type nasopharyngeal carriage in unvaccinated individuals (i.e. indirect effects). However, such data are lacking in Asia and there is little evidence available in children too young to be immunized. To establish a comparator for assessing PCV10 indirect effects in this populations, we measured prevalence and serotype distribution of pneumococcal colonization in young infants prior to the introduction of PCV in Nepal.

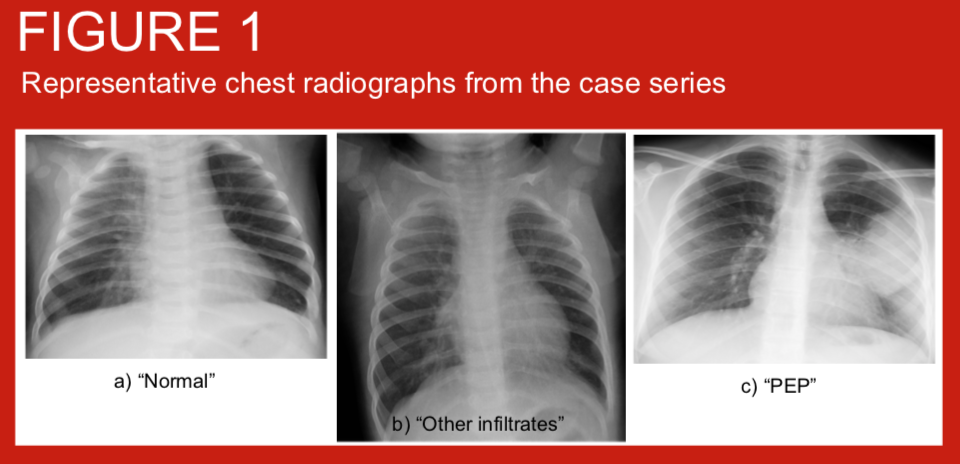

Use of WHO criteria for the interpretation of chest radiographs from children <5 years of age with pneumonia allows comparison of primary endpoint pneumonia (PEP) incidence across settings and over time. We applied these criteria to chest radiographs from children hospitalised with clinician diagnosed pneumonia before and shortly after the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV10) into the Nepal routine infant immunisation schedule from August 2015. Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine has been given since 2009.

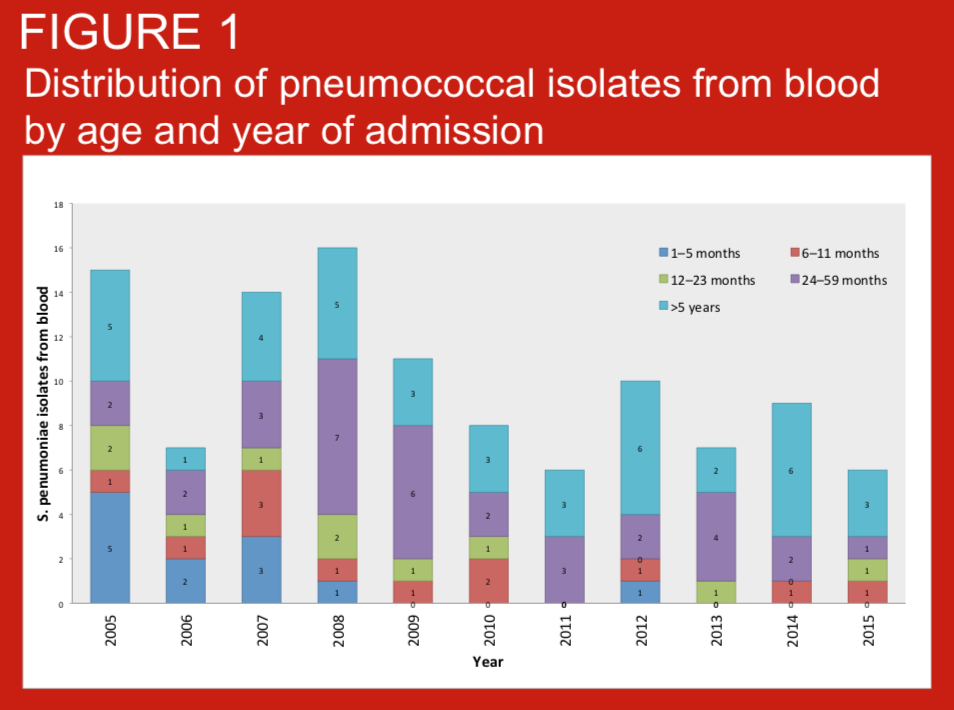

Invasive bacterial disease (IBD) are important causes of hospitalization in Nepali children. In Nepal, Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccination was introduced in 2009, and the 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV10) in 2015. Childhood invasive bacterial disease (IBD) surveillance at Patan Hospital Nepal has occurred since 2005.

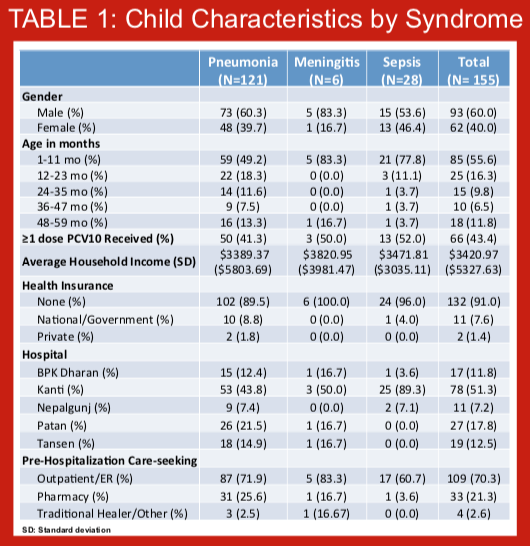

Few studies have assessed the economic consequences of pneumococcal disease and the economic impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV), particularly in South Asia. Despite introducing the PCV-10 vaccine into its National Immunization Program in 2015, no information on the cost of pneumococcal disease, specifically the cost of pneumonia, meningitis, and sepsis, are available for Nepal. The role of economic evaluations has become critical to introducing new vaccines and sustaining existing vaccine programs. As part of a larger study (PneumoNIA) aimed at estimating the epidemiologic and economic impact of PCV-10 in Nepal, we estimated the cost of hospitalized pneumonia, meningitis, and sepsis among children 1-59 months in Nepal. The results presented here are preliminary using data from the first month of data collection.

When children are hospitalized due to pneumococcal disease, families may have to use savings, sell property, or even take out loans in order to pay for their hospital care. Additionally, their time spent away from production may impact negatively on their revenues. Out-of-pocket (OOP) healthcare spending has the potential to be catastrophic to households, potentially pushing households into poverty (Figure 1). Few studies globally have assessed the risks of experiencing catastrophic expenditures from hospitalized pneumonia, particularly in South Asia. Despite introducing the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine-10 (PCV-10) into the routine National Immunization Program in 2015, no information on the economic burden households bear, are available for Nepal. As part of a comprehensive PCV impact evaluation (PneumoNIA) program, we estimated the OOP health payments per pneumococcal events and the proportion of households experiencing catastrophic health expenditures (CHE) from hospitalized pneumonia, meningitis, and sepsis in Nepal. The results presented here are preliminary using data from the first month of data collection.

Data on the economic impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) for families and the healthcare system are important to sustain support for a vaccine program that began rolling early 2015. We present methods used to estimate the economic impact of PCV in Nepal to illustrate data collection challenges. This study is embedded in the PCV impact evaluation (PneumoNIA) program to estimate the cost of pneumococcal disease and the proportion of household experiencing catastrophic health expenditure due to pneumococcal disease. The discussion surrounding data collection challenges is preliminary as data collection activities for this study have not concluded.

A pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV10) immunogenicity study in 2010 showed that a 2+1 schedule (two dose priming at 6 and 14 weeks with a booster at 9 months) was non-inferior to a 3+0 schedule (3 dose priming at 6, 10 and 14 weeks) schedule in early infancy, but superior in late infancy. The introduction of intramuscular inactivated polio vaccine at 14 weeks of age in Nepal has led to the rescheduling of the second priming dose of PCV10 to 10 weeks of age.

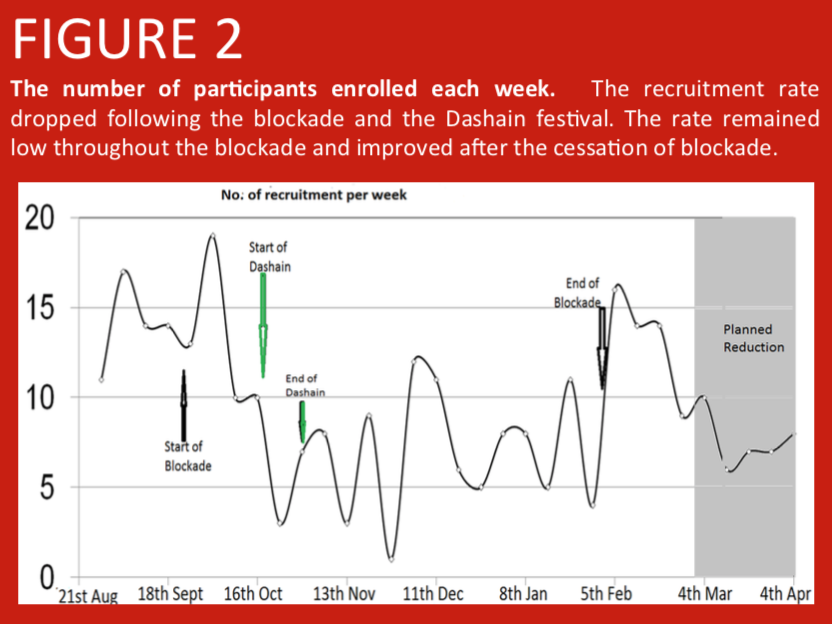

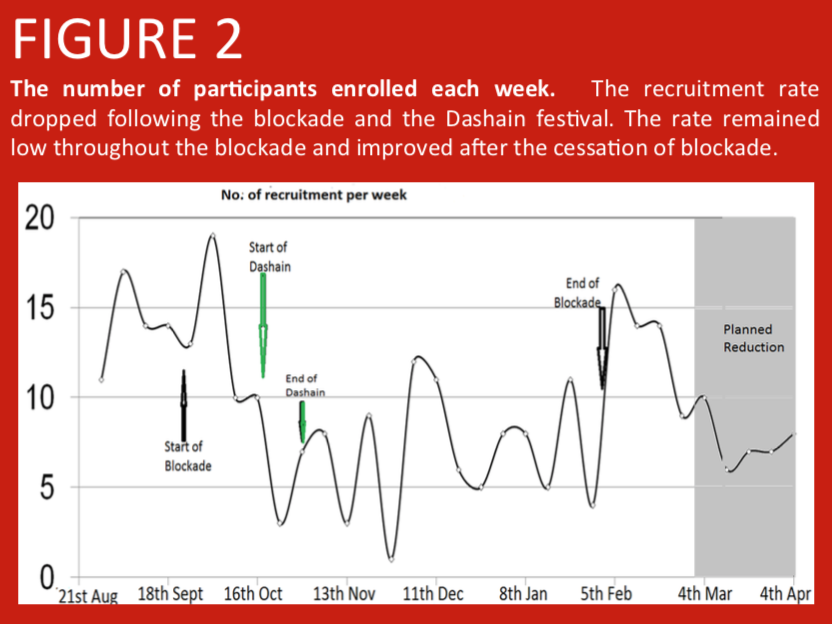

A randomised controlled trial was conducted in Nepalese infants comparing PCV10 priming at 6 and 10 weeks, with PCV10 priming at 6 and 14 weeks of age. Here we address the large scale factors that have influenced study recruitment. In Nepal, prior to the start of enrolment in the study, over 400 earthquakes in April and May 2015 led to population shifts between urban and rural regions as city dwellers moved back to be with their families in the villages. Additionally, a blockade at the Nepal-India border due to a protest in the Terai region from September 2015 led to fuel and consumable shortages making it difficult for parents to attend immunization clinics. Further population shifts occurred during the Dashain festival (an annual Hindu festival during which many individuals leave the cities to be with their family in remote villages).

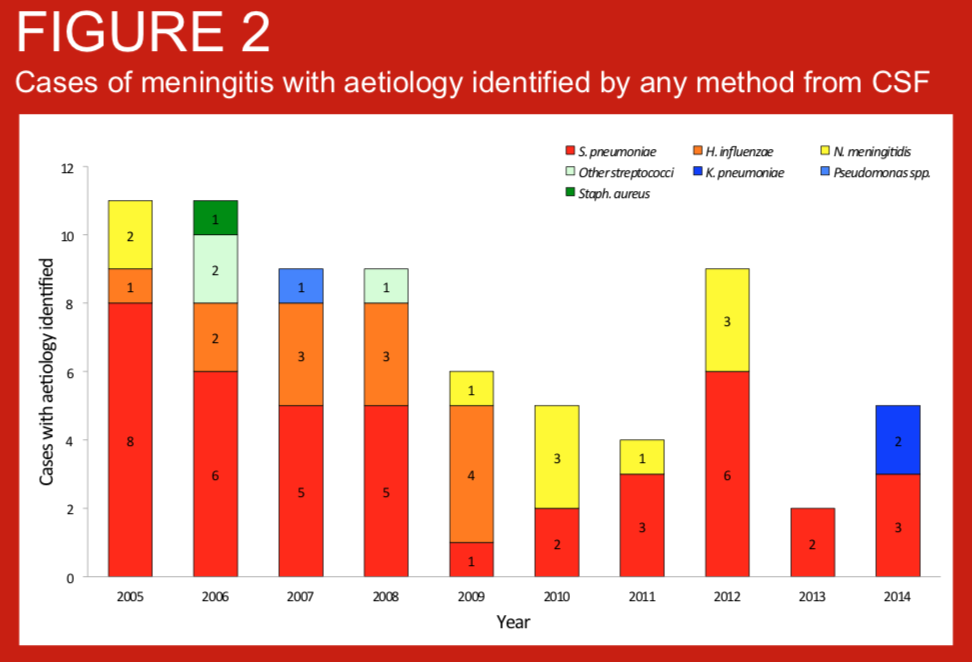

Bacterial meningitis is an important cause of mortality and morbidity globally but three of the most important pathogens, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type b and Neisseria meningitidis are vaccine-preventable. Nepal introduced routine infant vaccination against H. influenzae type b (Hib) in 2009, and routine infant pneumococcal conjugate vaccination (PVC10) in 2015. We present data on the bacterial aetiology of meningitis in children admitted to Patan Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal, for the 10 years preceding the introduction of PCV10.

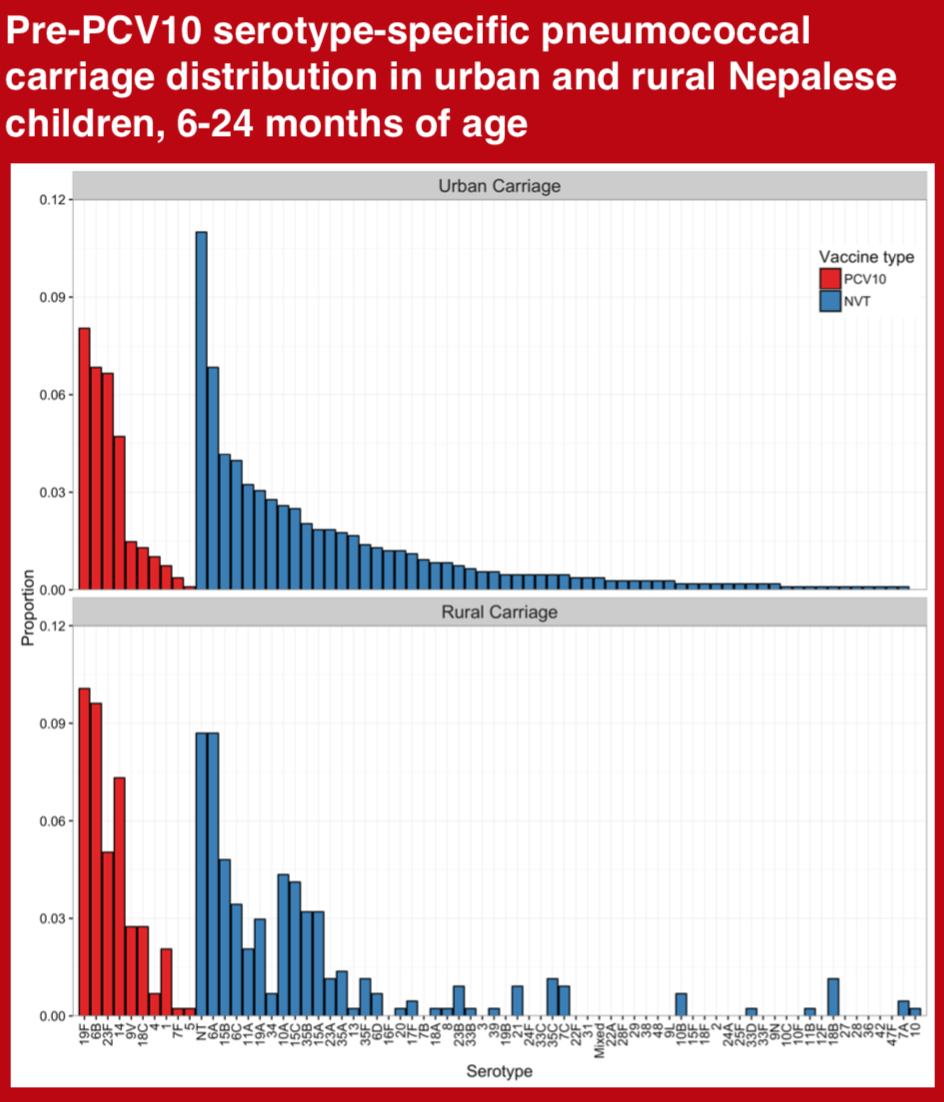

Assessment of Pneumococcal nasopharyngeal carriage prevalence is an important method for monitoring pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) programs. We aimed to measure the prevalence and serotype distribution of pneumococcal carriage in young children from urban and rural Nepal, prior to nationwide introduction of the 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV10).

The diversity of invasive pneumococcal serotypes has significant geographic variation. Accurate depiction of this spectrum and its distribution according to age is integral to maximizing the impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in specific settings.

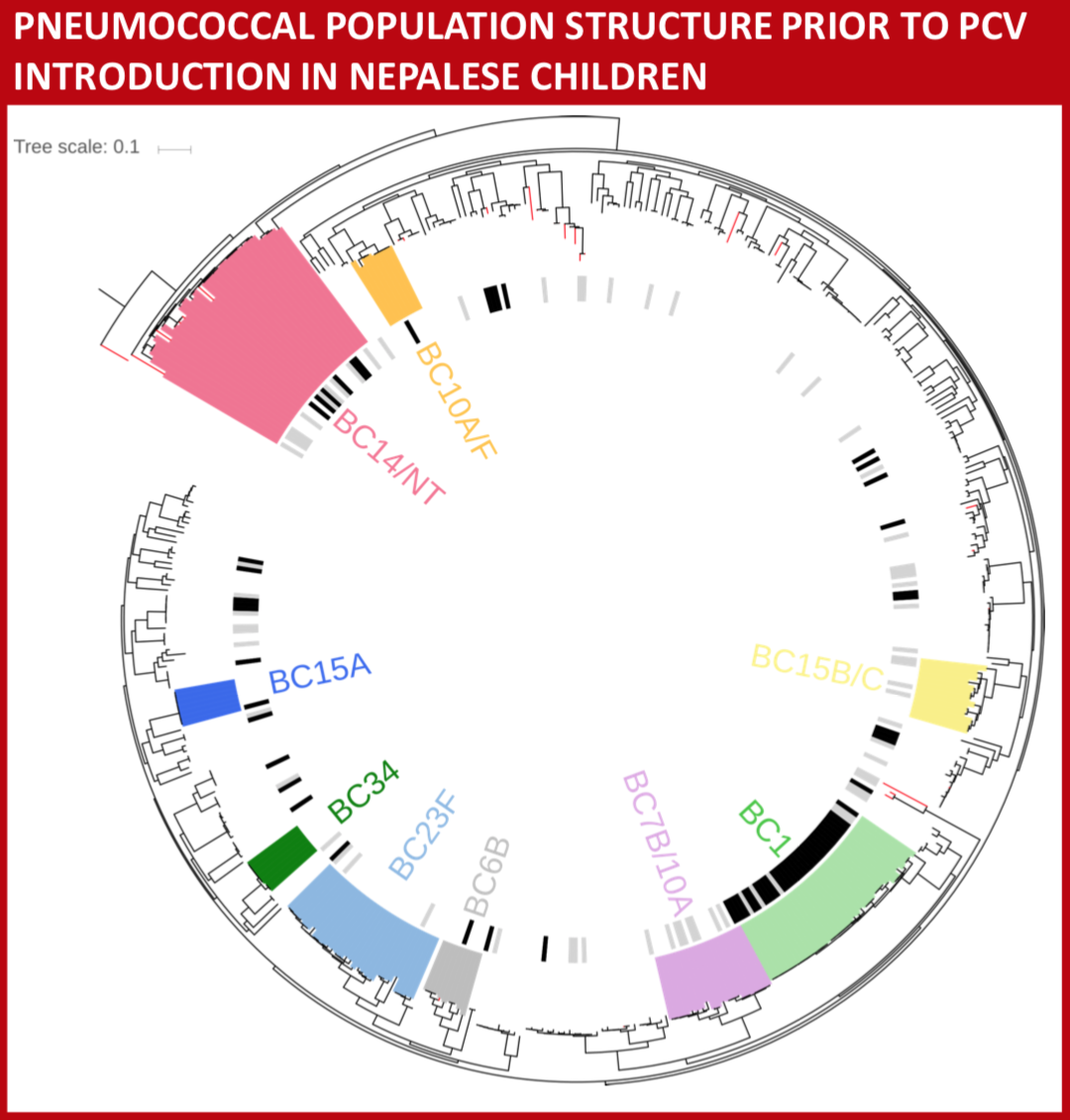

We aimed to evaluate the molecular epidemiology of pneumococci in Nepal from nasopharyngeal carriage in healthy young children and relate that to the pneumococci isolated from the nasopharynx of children with pneumonia or invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) prior to pneumococcal vaccine introduction.

Some pneumococcal serotypes are infrequently carried by healthy children but represent a large proportion of disease isolates. Detection of serotype-specific pneumococcal colonization in children with pneumonia, although not diagnostic of etiology at an individual level, likely enriches the group of cases for true pneumococcal pneumonia. We aimed to assess serotype-specific carriage among Nepalese children admitted to hospital with physician diagnosed pneumonia and compare it with that of healthy community controls prior to PCV10 introduction.

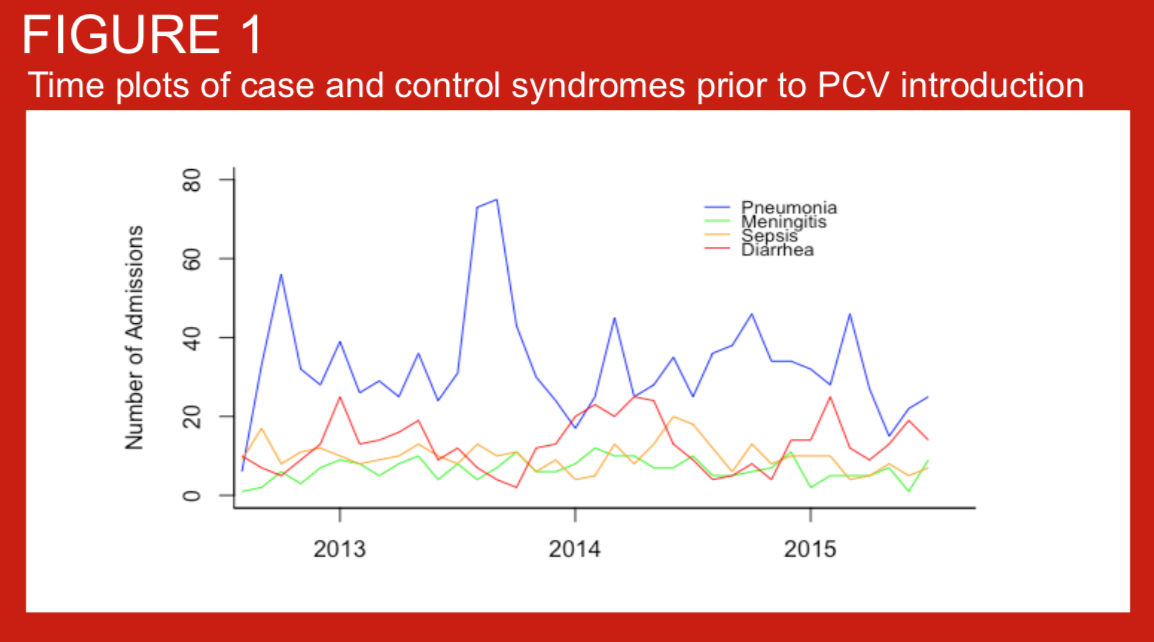

In August 2015, the 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV10) was introduced in the Kathmandu valley using a 2+1 schedule, with immunization at 6 weeks, 10 weeks, and 9 months of age. Children less than 1 year old at the time of introduction were recommended to receive 1-3 doses whenever possible. Data on the impact of PCV on disease endpoints in children under 5 years of age are lacking from Asia. The introduction of PCV10 in Nepal provides an opportunity to measure the impact of this vaccine on pneumonia, meningitis, and sepsis hospitalizations using administrative data from a low-income country in Asia. To inform analytical approaches for measuring vaccine impact on these endpoints, we studied hospitalizations for several syndromes in the period prior to PCV10 introduction.

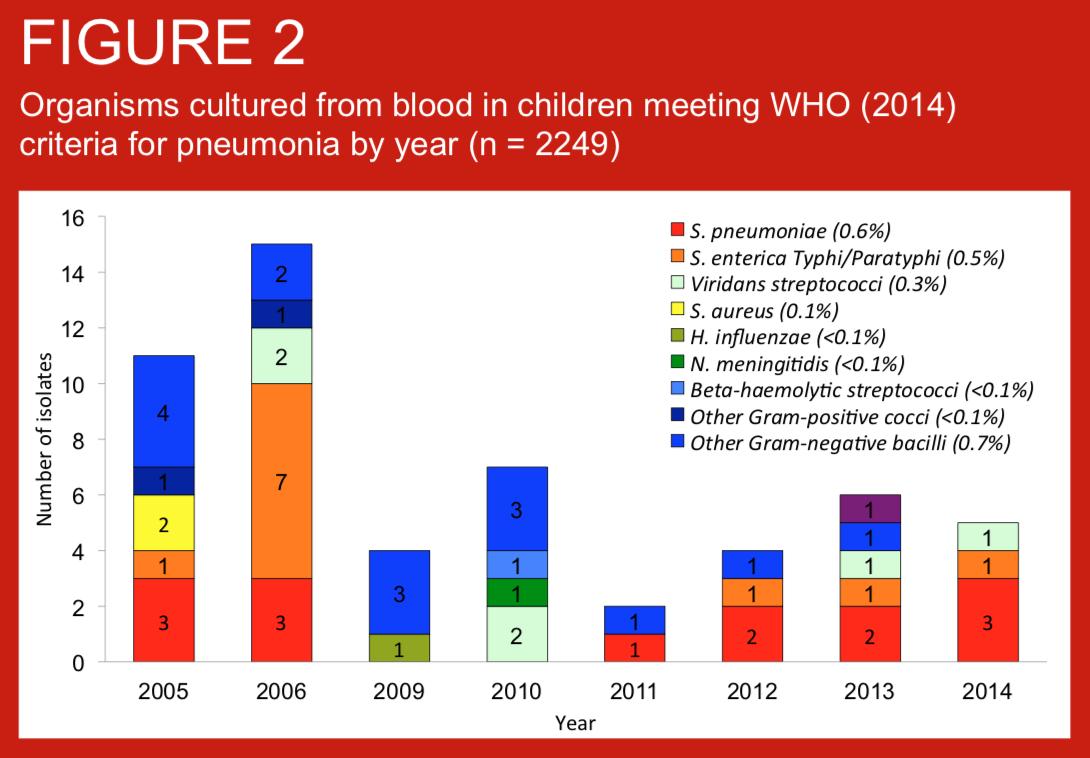

Standardised definitions of pneumonia are required for clinical care, comparisons of pneumonia incidence across settings, and other reasons including assessment of vaccine impact. We describe the prevalence, age distribution of pneumonia as defined by WHO (2014) criteria in children consecutively admitted with suspected invasive bacterial disease (IBD) to Patan Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal. We also present blood culture data for these case series. Routine infant immunisation against Haemohilus influenzae type b was introduced to Nepal in 2009.

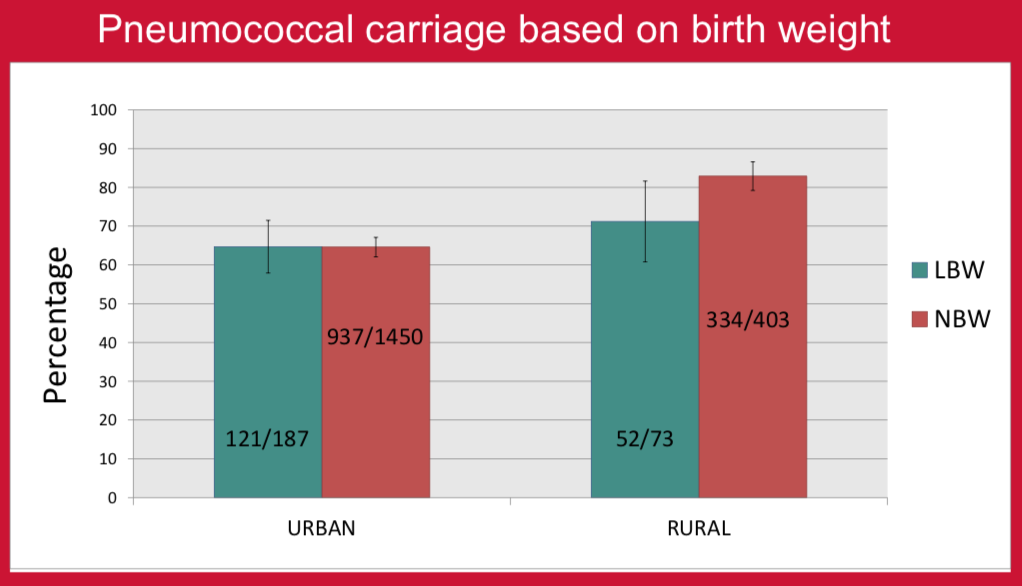

There are only a few studies comparing the association of nasopharyngeal carriage of pneumococcus with gestational age or birth weight1,2. The aim of this study was to look for any association of nasopharyngeal carriage with term/preterm gestation and normal/low birth weight in healthy children in urban and rural populations in Nepal before the introduction of PCV10 vaccine. PCV10 vaccine was introduced into the national immunization program of Nepal in January 2015. Vaccine implementation commenced in different districts in a phase wise manner. In Kathmandu (the capital city), the program started in August 2015 and in Okhaldhunga (one of the rural districts) in October 2015.

Pneumococcal pneumonia is an important cause of childhood morbidity and mortality in South Asia. We assessed the impact of 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV10) on serotype-specific nasopharyngeal (NP) carriage in children admitted to hospital with pneumonia. PCV10 was introduced in Kathmandu in August 2015 at 6 weeks, 10 weeks, and 9 months of age.

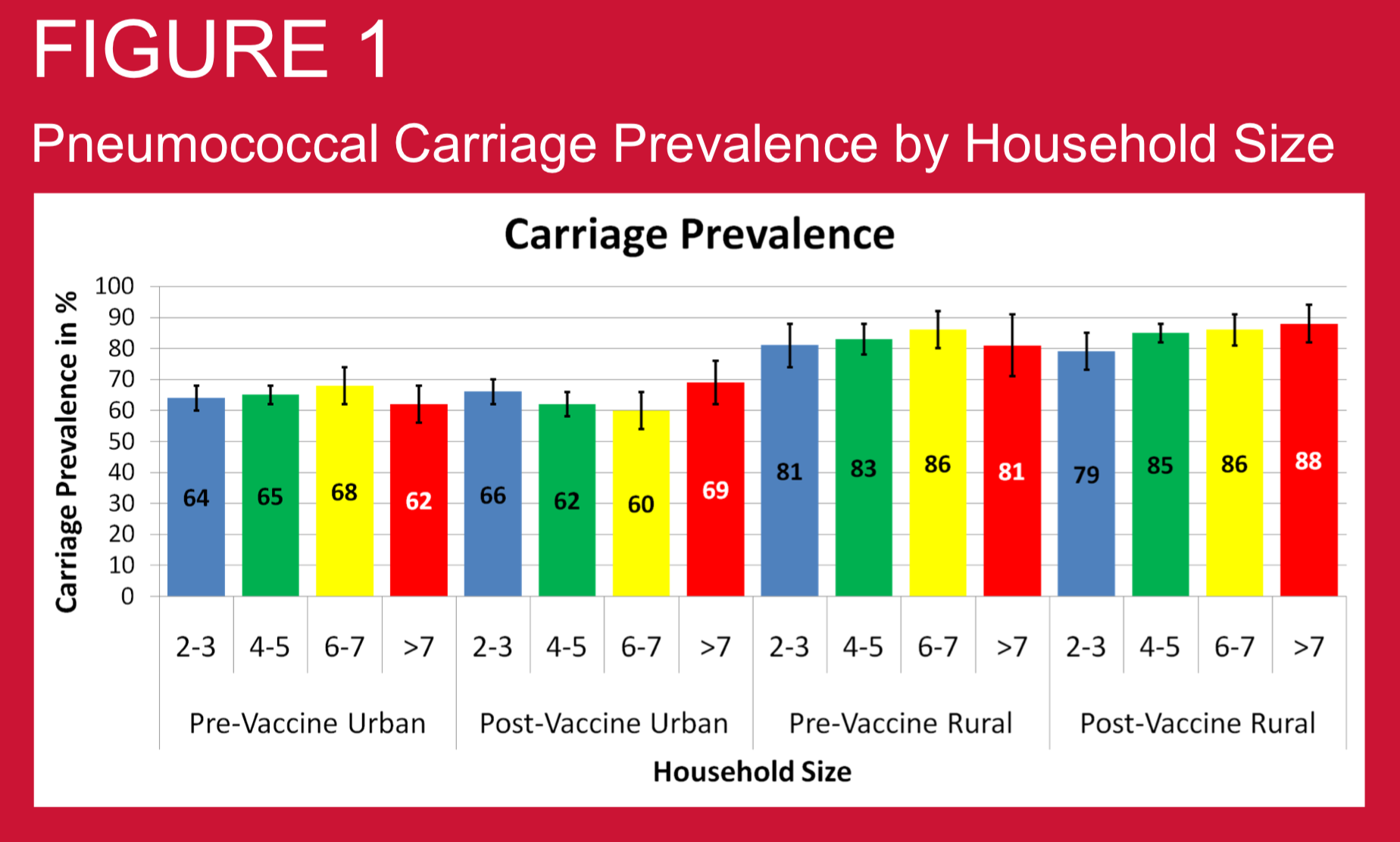

Crowding may be important determining factor for pneumococcal disease risk through aerosol transmission of pneumococci. Hence household crowding may be an important factor determining nasopharyngeal (NP) carriage prevalence of pneumococcus. We investigated this relationship in Nepali children using samples collected before and after PCV10 vaccine introduction.

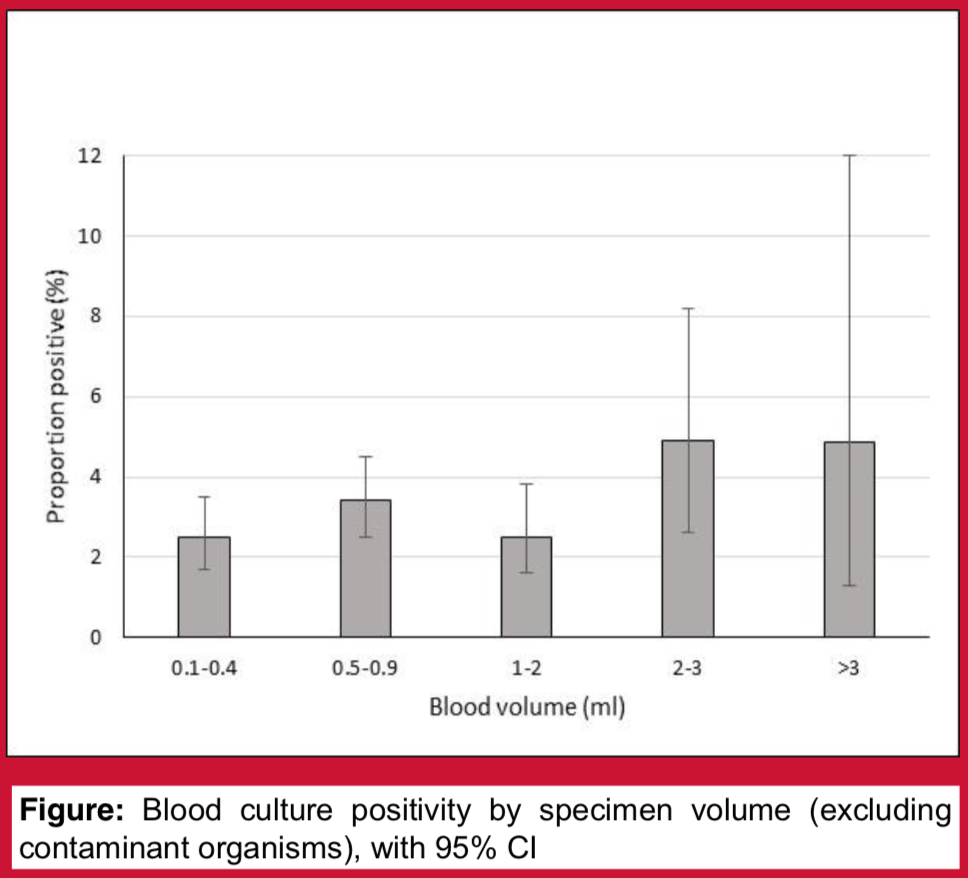

Blood cultures form the cornerstone of pneumococcal disease surveillance programmes. To optimise detection of Streptococcus pneumoniae, it is important to understand the factors affecting blood culture yield. Blood culture volume surveys have been performed periodically as part of an invasive pneumococcal disease surveillance programme at Patan Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal. These surveys are also intentionally used as an opportunity to educate staff about good blood culture collection technique. We hypothesised that increasing specimen volume is associated with increased blood culture yield, and that blood culture contamination rates would be lower during specimen volume survey periods.

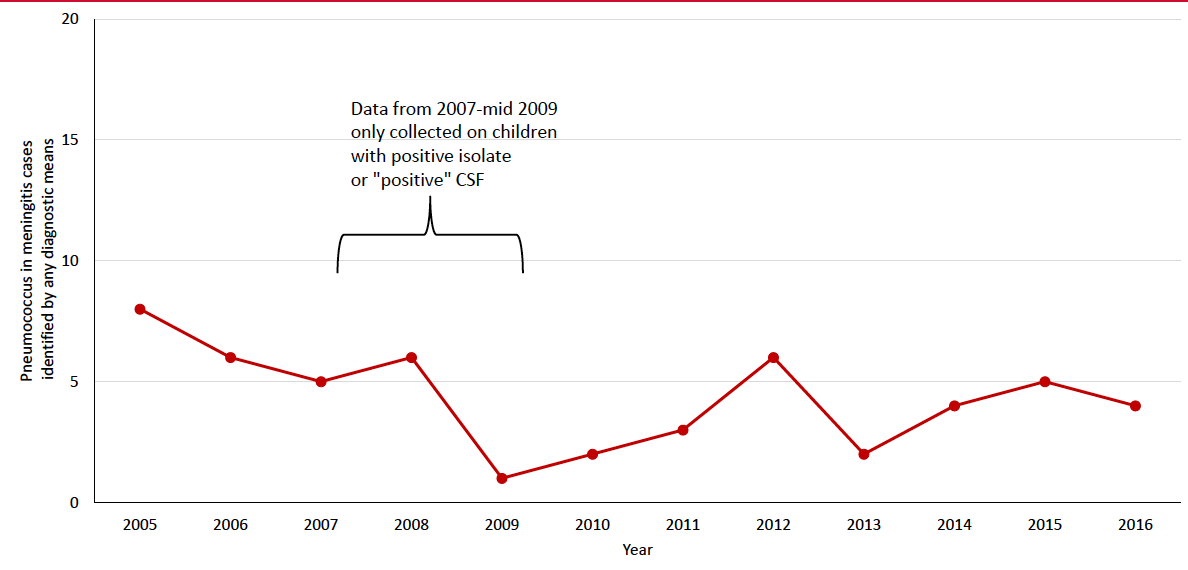

Bacterial meningitis is an important cause of mortality and morbidity in children throughout the world. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), and Neisseria meningitidis are the major causes of childhood meningitis and are vaccine preventable. Nepal introduced Hib vaccine in 2009 and 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV10) in 2015. We examined meningitis pathogens among children admitted to Patan hospital in Kathmandu, Nepal during 2005-2016 and assessed the impact of PCV10 on pneumococcal meningitis.

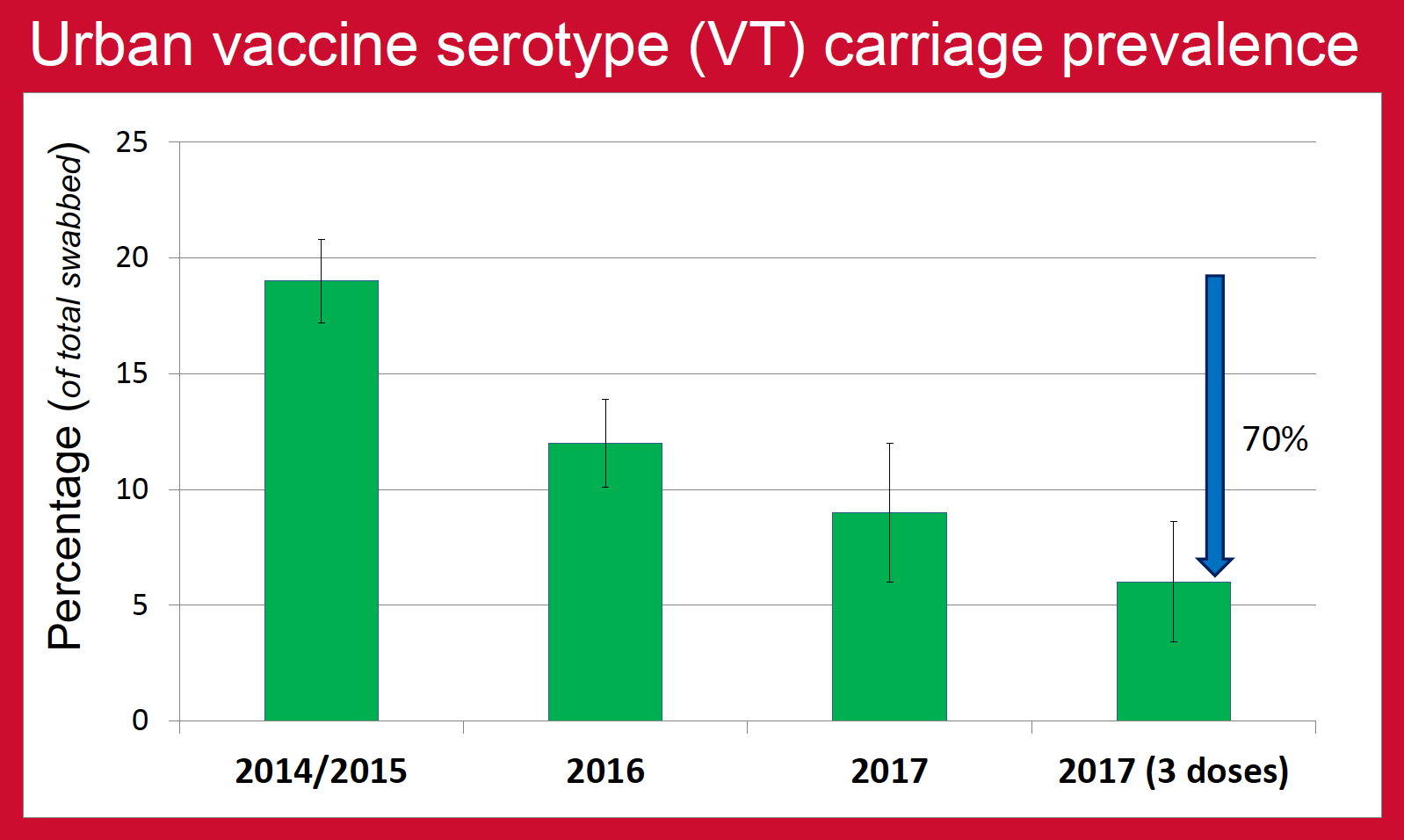

Nasopharyngeal carriage prevalence of pneumococcus is one of the major factors that determine the burden of pneumococcal diseases in the community. This is especially true for pneumococcal serotypes contained in PCV (vaccine serotypes, VT) as the majority of invasive pneumococcal diseases (IPD) are caused by these serotypes. Nepal introduced PCV10 vaccine in January 2015, the rollout reaching Kathmandu (urban) in August 2015 and Okhaldhunga (rural) in October 2015. The aim of this study was to determine the impact of PCV10 on VT carriage prevalence in urban and rural community-dwelling children of Nepal as an indirect measure of the vaccine’s effectiveness against pneumococcal diseases.

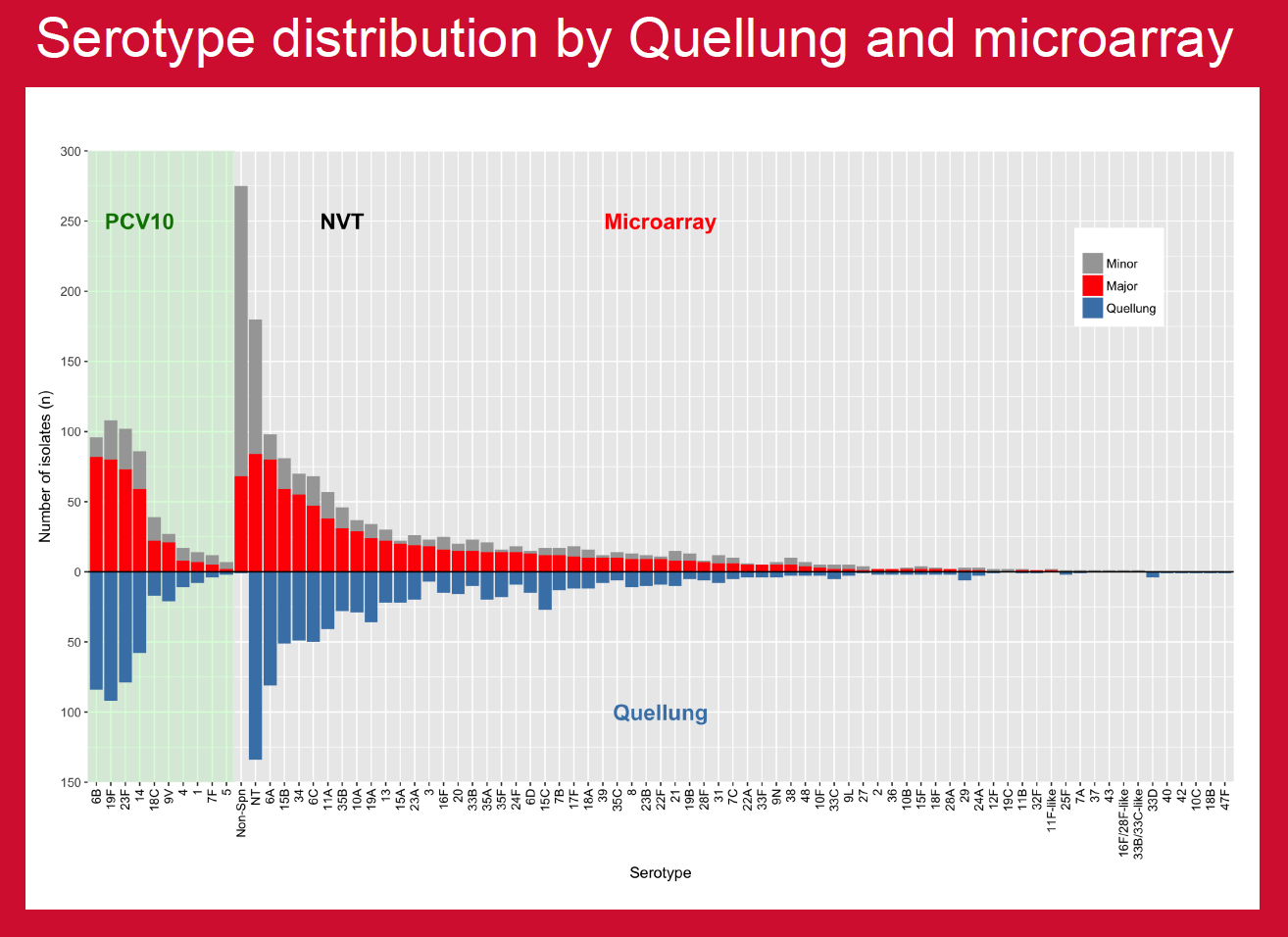

PCV10 was introduced in Nepal in 2015 and projects were in place to assess multiple aspects of vaccine impact. This study compared established in-country capacity for conventional serotyping with molecular serotyping by microarray to investigate potential benefits in carriage studies.

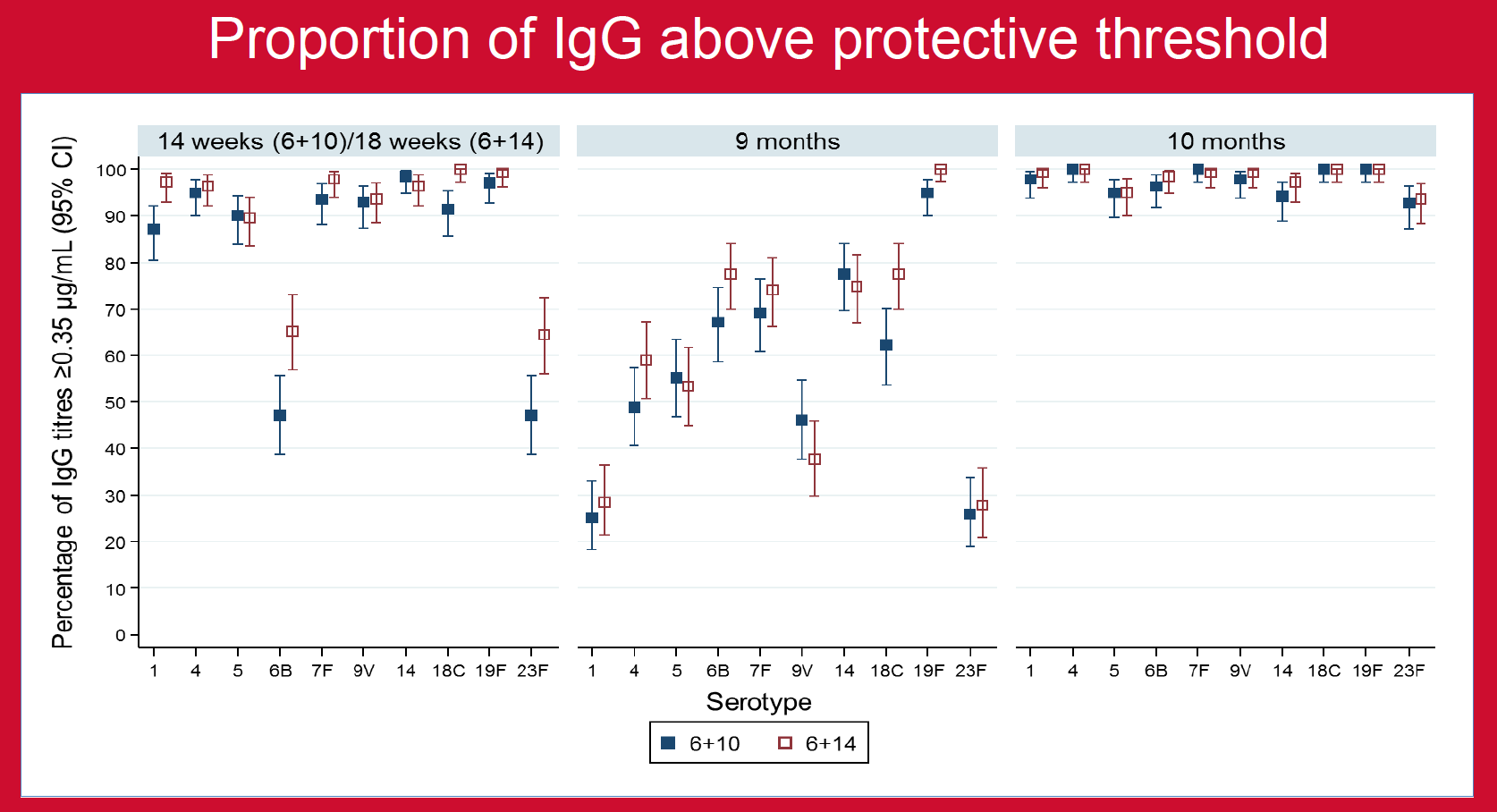

Nepal introduced PCV10 in 2015 using a unique 3-dose schedule (4-week interval between 2-priming doses; 6 weeks/10 weeks/9 months). A previous Nepal study demonstrated better and longer-lasting immunity after the third dose of a 2p+1 schedule (8-week interval between priming doses; 6w/14w/9m) than after the 3p+0 schedule (6w/10w/14 w) used in most GAVI countries; both schedules are now who recommended. However, as injectable polio was also being added to Nepal’s EPI schedule at 14 weeks, it was felt that going from one injection to three would be programmatically difficult for both parents and vaccinators, so a 6w/10w+9m schedule was chosen.

A single centre open-label, parallel-group, randomised, controlled trial was undertaken to determine whether the 6w/10w schedule is noninferior to the 6w/14w priming schedule, each followed by a booster dose at 9 months of age (9m).

Nepalese infants receive ten-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV10) with a 1-month interval between the first two doses for programmatic reasons. While the standard dosing schedule—when an infant is 6 weeks, 14 weeks, and 9 months—should be implemented where possible, findings from this trial showed that immunological responses after the booster dose at 9 months were similar in the standard and accelerated schedules. Therefore, the accelerated schedule used in Nepal is expected to provide herd protection.